Skip to content

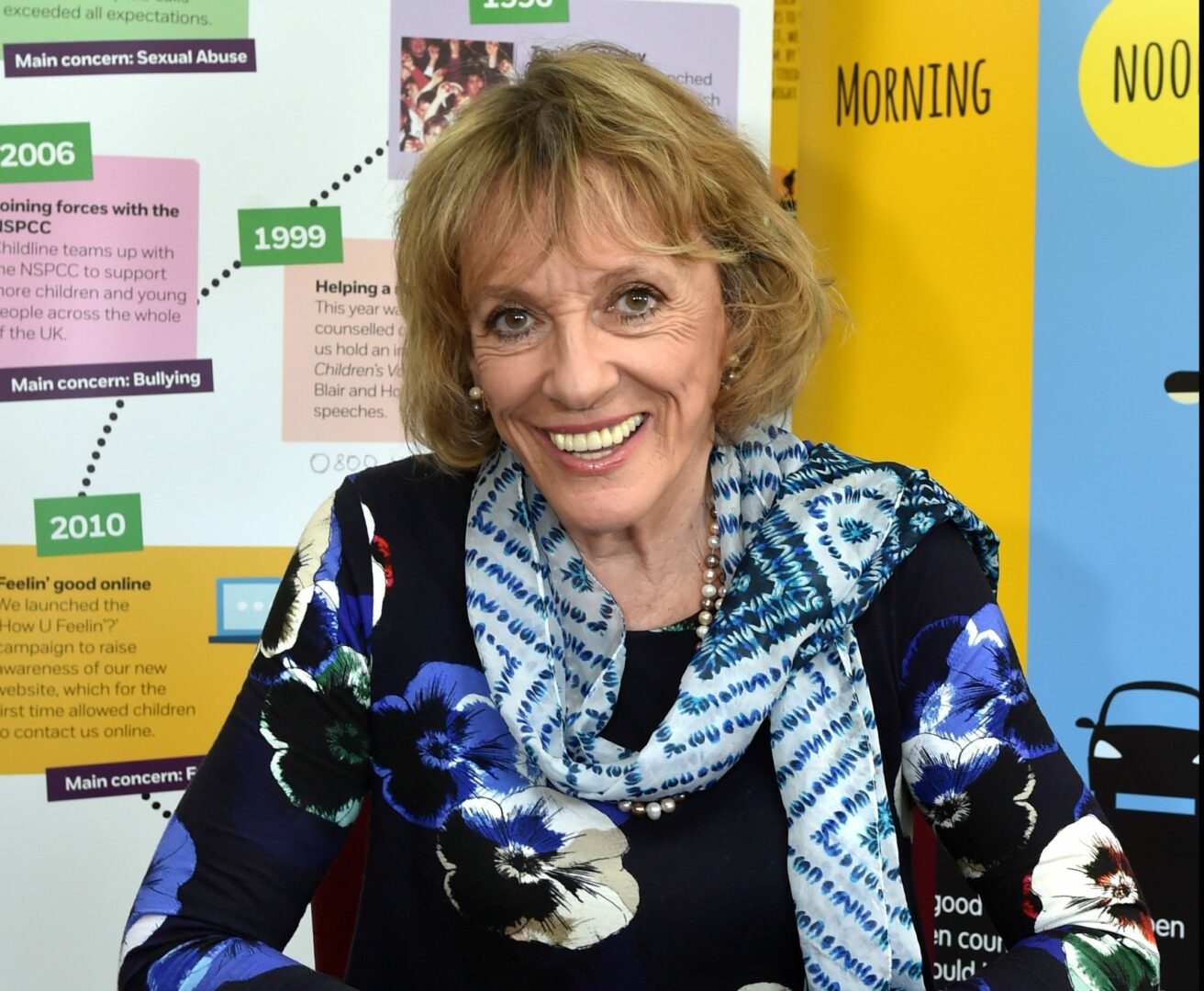

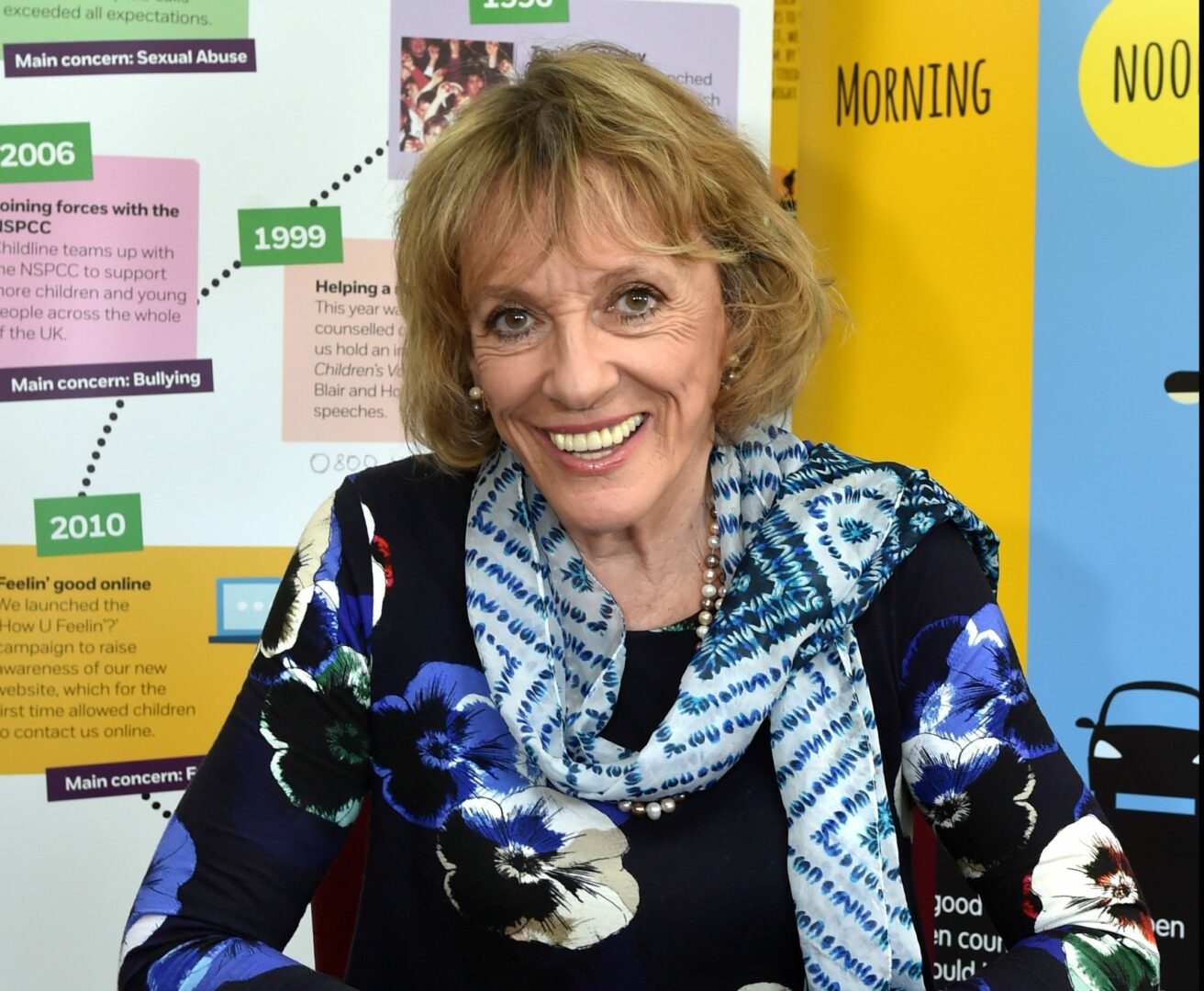

The broadcaster Dame Esther Rantzen says she has joined the Dignitas assisted dying clinic in Switzerland.

The 83-year-old told the BBC she is currently undergoing a “miracle” treatment for stage four lung cancer.

If it does not work, “I might buzz off to Zurich”, where assisted dying is legal, she told Radio 4’s The Today Podcast.

But she said she was looking forward to this “precious” Christmas, which she hadn’t thought she would live to see.

Assisted suicide is banned in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, with a maximum prison sentence of 14 years. While there is no specific offence of assisted suicide in Scotland, euthanasia is illegal and can be prosecuted as murder or manslaughter.

Dignitas is a not-for-profit organisation that provides physician-assisted dying to members who, in its words, have illnesses “that will lead inevitably to death, unendurable pain or an unendurable disability” and who have made a “reasoned request” with medical proof.

Speaking about her decision to join Dignitas, Dame Esther said it was driven in part by her wish that her family’s “last memories of me” are not “painful because if you watch someone you love having a bad death, that memory obliterates all the happy times”.

The broadcaster said if she did decide to have an assisted death at Dignitas that would put “my family and friends in a difficult position because they would want to go with me, and that means that the police might prosecute them”.

Dame Esther, who is best known for presenting the BBC Show That’s Life! for 21 years and launching the charity ChildLine, said she believed people should be given the choice about “how you want to go and when you want to go”.

“I get all the arguments about… not wanting to be a burden and pressure being applied and all that. But… you can come to the wrong conclusion.

“If you just base everything on the worst case scenario, you’ve got to have a look at the advantages as well.”

Campaigners for assisted dying say a change in the law would give people with terminal illnesses or who are suffering greater control over how and when they die.

But opponents argue a change in the law would threaten vulnerable people.

Dame Esther’s daughter, Rebecca Wilcox, told the BBC that there was a “legal murkiness surrounding assisting dying”.

“I support mum’s decision,” she said, but added: “I’m not legally allowed to say I’d go with her, that I would hold her hand – and that is absolutely ridiculous.

“I should be able to sit with my mother in her last moments.

“I can’t go to prison, I can’t go through a court case at the worst point of my life, when I’ve lost my person and I’m suddenly being prosecuted with her death.

“It’s unfathomable. I can’t believe this is the situation we’re in.”

In response to Dame Esther’s interview, Levelling-up Secretary Michael Gove said he thought it would be “appropriate” for the Commons to “revisit” the issue of assisted dying.

“I have great respect and affection for Dame Esther,” he said. “I take a slightly different view – I am not yet persuaded of the case for assisted dying but I do think it’s appropriate for the Commons to revisit this.”

Baroness Ilora Findlay, a crossbench member of the Lords and former president of the Royal Society of Medicine, told the Today programme the evidence from countries where the law had changed on assisted dying showed “that you just cannot regulate this really properly”.

Baroness Findlay said in Canada, where assisted dying became legal for those with terminal illnesses in 2016 and was expanded to those with serious and chronic physical conditions in 2021, the situation was “out of control”.

Instead, she said better access to end-of-life care was needed.

“We’re still relying on voluntary donations to make sure that people can live well for as long as they have,” Baroness Findlay added.

Euthanasia – the act of intentionally ending a life to relieve suffering – is legal in Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

Helping another person to kill themselves – assisted suicide – is permitted in Switzerland, while some form of assisted dying for terminally ill adults is legal in a number of US states, including Washington, California and Oregon.